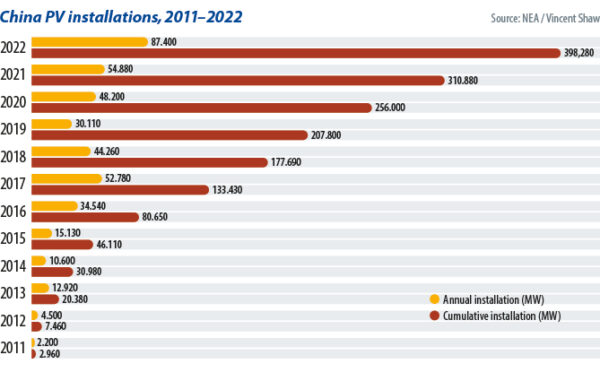

China is set to become the first country to install 100 GW(AC) of solar in a year. It is the world’s biggest solar market and exporter of most of the world’s PV wafers, cells, and modules. China’s photovoltaic industry has been 20 years in development and has rocketed in the last decade to include exports of PV production equipment and process know-how.

First steps

The industry had its beginnings in 1968 when researchers from the Institute of Semiconductors of the Chinese Academy of Sciences discovered high-resistance n+/p-type solar cells had better radiation resistance than p+/n-type cells. That made the former suitable to power the nation’s satellites during the Cultural Revolution.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the Chinese government established state-owned solar cell factories in Ningbo, in Zhejiang province, and in Kaifeng, Henan, to make small cells and modules for research purposes. A 10 kW site in Yuzhong, 40 km from the city of Lanzhou, is China’s oldest solar plant. It was built by the Gansu Provincial Institute of Natural Energy in Yuzhong in 1983, and today produces 70% of its original output.

PV industrialization

The industrialization of Chinese PV began with Zhengrong Shi’s foundation of Suntech Power in 2000, with backing from the Wuxi municipal government. The University of New South Wales (UNSW) graduate oversaw the opening of Suntech’s first 10 MW annual production capacity cell line in 2002, producing the same output as the total Chinese cell capacity of the previous four years.

In December 2005, Suntech became the first private Chinese company to list on the New York Stock Exchange. Suntech contemporaries LDK – founded in Jiangxi – and Hebei-based Yingli also went public in the United States, and the trio became the most important companies in the Chinese industry for a time.

Rapid growth

The three companies led China’s first golden age of solar, from 2002 to 2008, with Longi, Trina Solar, Canadian Solar, and JinkoSolar among the rivals to emerge. Chinese businesses, with their manufacturing cost advantage and supportive government policy, established an international advantage as demand for PV boomed in Europe and the US.

Initially midstream manufacturers, Suntech, LDK, and Yingli expanded upstream in response to silicon supply constraints, signing long-term supply deals and establishing their own polysilicon operations.

Those investments weighed heavily as the global financial system suffered a debt crisis in 2008, severely dampening demand for solar as debt-saddled nations swiftly withdrew clean energy subsidies. With the polysilicon price tumbling 90% within months, Suntech, LDK, Yingli, and others faced the risk of bankruptcy.

The subsequent imposition, by US and European lawmakers, of anti-dumping and countervailing duties on Chinese solar products, in 2011 and 2012, meant China’s PV manufacturers were suffering their darkest hour and many disappeared.

Reset button

Beijing responded by looking inward and ramping up the solar generation capacity targets set by the 12th and 13th national five-year plans, for the years 2015 and 2020. The introduction of metering subsidies and green certificate trading plus policy to back household PV and grid consumption of clean power further boosted domestic demand.

Regional authorities and state entities including the National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Finance, Ministry of Science and Technology, and National Energy Administration (NEA) drove initiatives such as the Golden Sun Project, Top-Runner Program, and Landscape Energy Base Project, to generate domestic demand for PV.

Burgeoning Chinese demand, a falling levelized cost of energy for solar and the recovery in overseas PV markets saw Chinese solar rebound after 2013.

On May 31, 2018, however, as visitors to the annual SNEC Shanghai solar exhibition returned home, the NEA chilled the market overnight by reducing PV subsidies, effective the following day. The move was made as more and more Chinese solar generation capacity was causing a mounting incentives bill for a government which wanted solar to compete without subsidy.

Grid parity

Since day one, Chinese solar manufacturers have aggressively tried to drive down production costs. GCL invested in continuous Czochralski silicon and fluidized bed reactor technology to reduce production costs for monocrystalline silicon from more than CNY 100 ($14.54) per kilogram to less than CNY 60/kg. Longi’s diamond-wire slicing of monocrystalline silicon ingots drove down the cost of wafers and Longi and peer Aiko Solar were among the first companies to invest in passivated emitter, rear contact (PERC) solar cells as a more efficient alternative to the then-mainstream BSF (back-surface field) incumbent.

Module makers including Trina Solar, JinkoSolar, and CSI developed new approaches including multi-busbar technology, half-cut cells, bifacial panels, stacked tiles, and bigger wafers.

The resulting products could produce electricity free of subsidy at the same cost as grid power in some areas in 2019, and in a majority of projects two years later, as Beijing halted subsidies.

Chinese Premier Xi Jinping in 2020 announced the nation would aim for peak carbon emissions by 2030 and carbon neutrality by 2060. The more-than 100 GW(AC) of new solar capacity expected this year could hit more than 130 GW next year, according to trade body the China Photovoltaic Industry Association.

Policy backing

The Chinese government’s ability to intervene in the domestic economy differentiates it from authorities in the US and Europe which must rely solely on fiscal policy and tax levers.

The nascent Chinese solar industry imported raw materials and production equipment and relied on exports to thrive, initially prompting Beijing to offer manufacturing-linked tax incentives.

When the US and EU slapped duties on Chinese products, policymakers ramped up sources of capital and used market competition to shore up PV companies while offering tax incentives and supportive land use policy. That crucial response established a full supply chain featuring Chinese raw materials and production equipment, and boosted domestic demand.

Home comforts

China has the largest single market in the world as well as a comprehensive industrial system and relatively low labor costs, which allow it to take advantage of its scale and gain a competitive advantage on cost. At the same time, the nation’s infrastructure is relatively robust. Joined-up transportation enhances logistics efficiency and further reduces costs and a well-developed communication system can help companies integrate supply chain resources and create cluster effects.

For a typical Chinese module manufacturer, the raw material for the monocrystalline silicon in its modules may come from silicon plants in Inner Mongolia or Qinghai. The silicon ingots come from plants in Yunnan and are processed into high-efficiency solar cells in factories near module plants in Jiangsu or Zhejiang.

Those materials are then sent to module fabs where they are processed with the auxiliary materials and accessories provided by nearby suppliers and finally shipped to the west and northwest of China, for the construction of ground-mounted power plants, or to ports in the east for export.

Private vs. public

Unlike most other domestic industries, the majority of China’s major PV players are private companies, with Miao Liansheng owning Yingli, Gao Jifan Trina Solar, and Peng Xiaofeng LDK. Private ownership means such companies have short decision-making hierarchies and can respond quickly to market changes, unlike their state-owned peers. Compared to more traditional industries, China’s solar sector has operated in a highly internationalized and specialized free market environment from the very beginning.

At the same time, most of China’s private entrepreneurs are experienced and open-minded and tend to be more courageous in the face of endless market challenges than their counterparts in traditional sectors. Neither the imposition of EU and US duties, nor the drastic changes in Chinese national policy, nor fluctuations in supply chain prices have been able to shake their determination to develop the PV business.

Most importantly, the Chinese government has shown a strong belief and determination to replace traditional fossil-fuel based electricity with renewable energy. This is the cornerstone of the development of the entire Chinese PV industry and it appears solid and reliable.

Key challenges

Chinese PV is still facing several uncertainties that may adversely affect future development, however.

Firstly, the global economy is currently facing the risk of recession. The World Bank, World Trade Organization, and OECD have lowered their growth forecasts for the global economy for last year and this, and have warned economies face an increasing risk of recession due to rising food and energy prices, inflation, and higher interest rates in developed nations.

The outlook for the Chinese economy is equally bleak. After a nightmarish experience with Covid-19 prevention and control last year, China is in the midst of a difficult recovery and a declining property market, sluggish car sales, and local government debt of crisis proportions are all testing the economy. The expected downturn will lead to a decline in demand for electricity, including renewable energy, which will directly affect the development of the solar sector.

At the same time, geopolitical risks also loom. The major solar markets of the EU, the US, and India have all announced an intent to develop their own PV supply chains. Does this mean that more trade protection policies will be introduced? Will there be more trade barriers erected against Chinese PV products?

Other challenges in China include whether the grid is capable of accommodating ever higher volumes of intermittent renewables generation capacity. Will mandatory energy storage ratios imposed by local governments on renewables sites – including PV – lead to significant cost increases that will hurt investment?

Despite the storm clouds, however, China’s achievement of 100 GW(AC) of annual solar installations is still worthy of congratulation from everyone associated with the energy transition and substantiates the bright future of the business in which we are engaged.

This content is protected by copyright and may not be reused. If you want to cooperate with us and would like to reuse some of our content, please contact: editors@pv-magazine.com.

7 comments

By submitting this form you agree to pv magazine using your data for the purposes of publishing your comment.

Your personal data will only be disclosed or otherwise transmitted to third parties for the purposes of spam filtering or if this is necessary for technical maintenance of the website. Any other transfer to third parties will not take place unless this is justified on the basis of applicable data protection regulations or if pv magazine is legally obliged to do so.

You may revoke this consent at any time with effect for the future, in which case your personal data will be deleted immediately. Otherwise, your data will be deleted if pv magazine has processed your request or the purpose of data storage is fulfilled.

Further information on data privacy can be found in our Data Protection Policy.